Spiny Waterflea

Identification

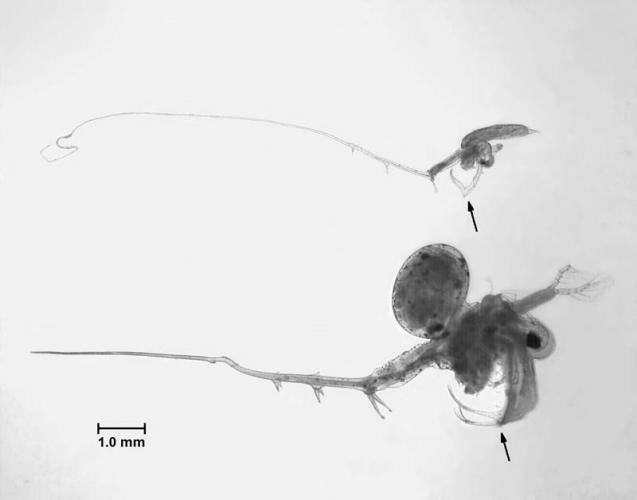

Spiny waterflea can grow to 12 mm in length. The long, spiny tail makes up roughly 70% of this species' body length and has 1-4 pairs of barbs running down it. Spiny waterflea has four pairs of legs on the underside of their body and is similar in appearance to the fishhook water flea, but lacks the “hook” at the end of its tail. Spiny waterflea can often be seen by the naked eye, and will readily accumulate in a blob-like structure on fishing line and downrigger cables dragged through infested water.

Biology

Origin

Northern Europe and Asia.

Habitat

Spiny waterflea prefer cold, and open (generally pelagic) waters, but can persist in a wide range of lentic (still-water) conditions.

LifeCycle

Spiny waterflea populations tend to peak between early September and early November. When food (other zooplankton) is readily available and temperatures are warm, males will feed while females reproduce through parthenogenesis, not requiring fertilization from their male counterparts. During this time, only females are produced (sex of offspring is determined by water temperature and prey availability). As water cools and food declines, more males will be produced. Females can produce between 1-24 embryos which can be found in their brood pouch—if successful, these embryos can be dropped into sediment as resting eggs where they often survive the winter. Eggs will hatch in spring/early summer.

Ecological Threat

Lake monitoring has shown the spiny waterflea, as a result of predatory behavior, to reduce species richness and population sizes within zooplankton communities. This has large implications for Lake Champlain (and other Vermont water bodies acting as fisheries) as it could significantly alter aquatic food web dynamics through direct competition with small fish for zooplankton. Reduction in water clarity is a notable effect of spiny waterflea, one with serious monetary implications. This reduction is water clarity is attributed to spiny waterflea due to the fact that it so voraciously predates on other algae grazers.

Vermont Distribution

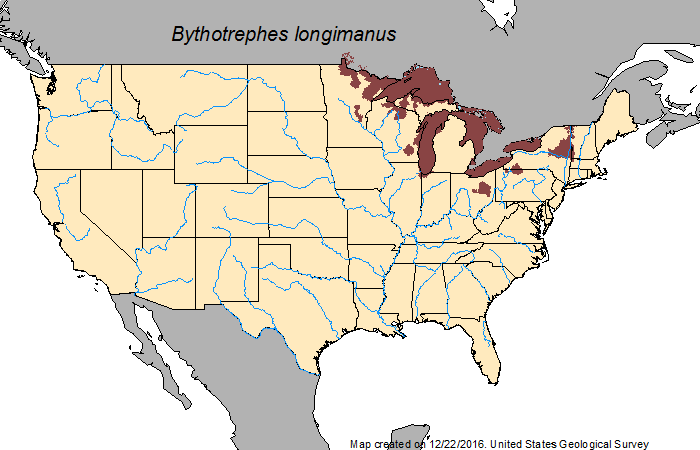

Spiny waterflea was first documented in Lake Champlain in 2014, where the only known population in Vermont exists. They are also found in the Great Lakes and many locations in the northern Midwest and southern Canada.

How You Can Help

For most aquatic invasive species, humans are the primary vector of transport from one waterbody to another. Many of these nuisance plants and animals can be unknowingly carried on fishing gear, boating equipment, or in very small amounts of water in a watercraft. The easiest and most effective means to ensure that you are not moving aquatic invasives is to make sure that your vessel, as well as all your gear, is drained, clean, and dry.

BEFORE MOVING BOATS BETWEEN WATERBODIES:

-

CLEAN off any mud, plants, and animals from boat, trailer, motor and other equipment. Discard removed material in a trash receptacle or on high, dry ground where there is no danger of them washing into any water body.

-

DRAIN all water from boat, boat engine, and other equipment away from the water.

-

DRY anything that comes into contact with the water. Drying boat, trailer, and equipment in the sun for at least five days is recommended. If this is not possible, then rinse your boat, trailer parts, and other equipment with hot, high-pressure water.

Interested in monitoring for aquatic invasives?

- Join the VIPs! Vermont Invasive Patrollers help search for new infestations so we can respond immediately and prevent them from becoming established.

Citations

Berg, D.J., and D.W. Garton. 1988. Seasonal abundance of the exotic predatory cladoceran, Bythotrephes cederstroemi, in western Lake Erie. Journal of Great Lakes Research 14(4):479-488.

Liebig, J., A. Benson, J. Larson, T.H. Makled and A. Fusaro. 2016. Bythotrephes longimanus. USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL. Revision Date: 6/4/2013

Walsh, J.R., S.R Carpenter, and M.J.V. Zanden. 2016. Invasive species triggers a massive loss of ecosystem services through a trophic cascade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 113(15):4081-4085.

Yan, N.D., R. Girard, and S. Boudreau. 2002. An introduced invertebrate predator (Bythotrephes) reduces zooplankton species richness.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2008. Predicting future introductions of nonindigenous species to the Great Lakes. National Center for Environmental Assessment, Washington, DC; EPA/600/R-08/066F. Available from the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA, and http://www.epa.gov/ncea.