Author: Carly Alpert, Aquatic Invasive Species Program ECO AmeriCorps Service Member 2021

November 2021

Oftentimes, native plants and their invasive counterparts appear nearly indistinguishable to an untrained eye. These physiological similarities may allow the invader to remain undetected for years. This ability to remain concealed, hidden from early detection, paired with their competitive edge in resource acquisition is what allows them to turn into nuisances, capable of altering entire ecosystems. This secretive similarity in the nature of plant growth is an example of a case between two similar looking aquatic plants, Elodea and Hydrilla, which caused some excitement this summer.

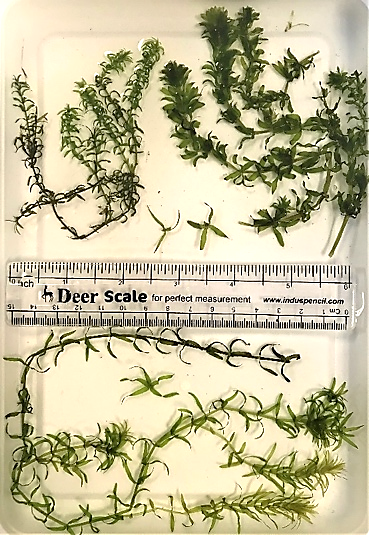

Photo of specimen samples of native Elodea nuttalli species (top left, and bottom) and invasive Hydrilla (top right). Photo Credit: K. Jensen

If you’ve ever paddled or boated along the shoreline of a Vermont waterbody and noticed a bed of bushy green stalks, chances are, you’re gazing at Elodea. There are two Elodea species native to Vermont: Elodea canadensis, known as Common waterweed, and Elodea nuttalli, known as Slender waterweed. Both may have leaves arranged in whorls of 3-4, though usually found as three. The edges of the leaves are normally smooth, though in some observations of Elodea nuttalli minute serrations, or teeth, are found in rare cases. It’s difficult to identify between these two native Elodea species because they are so similar physiologically. To further confusion, in the case of Hydrilla, (scientific name Hydrilla verticillata) there can be 3-8 leaves per whorl though usually observed in whorls of 4-5. The leaf edges have observable serrations along the tip of the leaves. This ambiguity of leaf number per whorl is one reason Elodea and Hydrilla are sometimes difficult to differentiate (see photo).

This summer, when a Lake Champlain Boat Steward found a Hydrilla looking specimen aboard a retrieving boat from Lake Champlain, and our expert biologists found another similar specimen in Lake Fairlee, “excitement” or maybe dread ensued. Since the physical look of the specimen was suspect, genetic analysis was necessary to confirm the identity of the plant, especially as intraspecific variation may blur lines between species even more so.

Hydrilla is a federally listed noxious weed that has yet to be identified in Vermont waters, though it wreaks havoc in southern states. Because of its many adaptive qualities, Hydrilla is a super invader, creating vast environmental and economic consequences. It grows in large, dense mats preventing sunlight from penetrating the water column, thus outcompeting native species. These mats are cumbersome to eradicate, costing roughly $1,000/acre to treat. Because of its density, Hydrilla is also a nuisance for boaters, paddlers, and anglers.

Hydrilla was first identified in the Connecticut River in 2016 in Glastonbury. Since then, the Connecticut Agriculture Experiment Station, (CAES) has surveyed from the Long Island Sound to as far north as Agawam, MA and reported 774 acres of Hydrilla. VTDEC assisted with the initial survey and reported on this effort in 2018 (former article found here). This is a serious concern for the Vermont/New Hampshire portion of the Connecticut river, as Hydrilla fragments can float along the river and re-root, or travel to new water bodies via transient boaters. According to Gregory Bugbee, scientist with CAES, “Hydrilla is the worst aquatic submersed plant in the southern parts of the United States.” Because of its submersed nature and perennial tubers which remain in the sediment for years, it is an extremely troublesome plant to remove.

The Northeast Aquatic Nuisance Species Panel coordinates the effort to monitor and manage the infestation and with Connecticut stakeholders developed the Connecticut River Hydrilla Five-Year Management Plan. In the northern section of the Connecticut River, Vermont and New Hampshire aquatic biologist’s annually team up to complete surveys and this year a survey of roughly 22 miles have been monitored near Brattleboro and Springfield with no evidence of Hydrilla. Efforts will continue in the Summer of 2022.

In the case of the suspicious specimen found this summer, the genetic testing found the specimen to be the native, Elodea nuttalli (whew!). The takeaway? Plant characteristics don’t always adhere to grow as outlined in keys, guides, and publications, especially when the growth may be affected by seasonal or temporal growing conditions. It’s always important to look at the entire plant from roots to shoots, to flowers and fruits, and if you are still stumped, call on an expert.

If you do find any suspicious aquatic plant, please report it to the VTDEC by calling (802) 828-1115 or emailing Kimberly Jensen at kimberly.jensen@vermont.gov. Be a steward of Vermont’s precious waterways and prevent the spread of Hydrilla and other aquatic invasive species by cleaning all recreational equipment every time you visit a new waterbody.

Learn more about Hydrilla and how you can get involved!

- Information on how to become a Vermont Invasive Patroller.

- “Clean Drain Dry” procedure to prevent the spread of invasives via boats.

- An informative video explaining the Hydrilla crisis in the lower Connecticut River.

- USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species factsheet on Hydrilla.

References

Heading off Hydrilla. Michigan Department of Environmental Quality.

Hydrilla in the CT River Watershed. Connecticut River Conservancy. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2021.

Lakes and Ponds Management and Protection Program. 2021. A Key to Common Vermont Aquatic Plant Species. Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation.

Skawinski, M. Paul. 2019. Aquatic Plants of the Upper Midwest. 4th edition. Wausau, Wisconsin.

Gleason, Henry A., & Arthur Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. 2nd edition. Bronx, N.Y. New York Botanical Garden.

Photo Credit: K. Jensen